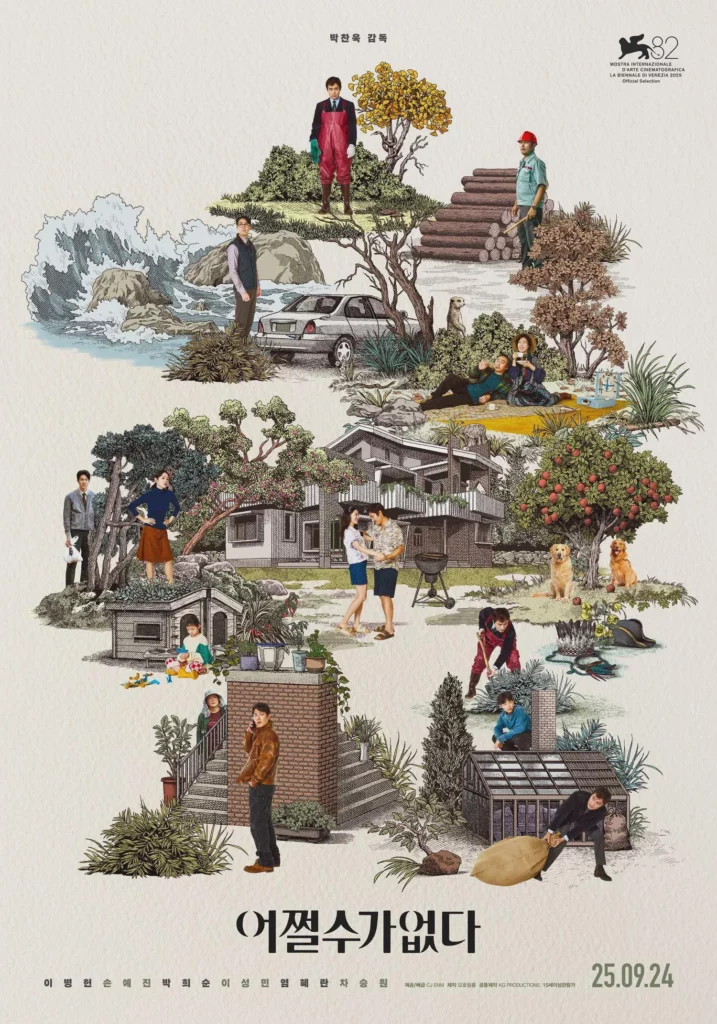

In No Other Choice, acclaimed South Korean director Park Chan-wook immerses us in a world fraught with moral tension, where every action matters and consequences quietly unfold.

There are no simple heroes or villains—only humans negotiating survival, ambition, and conscience. Through striking visuals and meticulous storytelling, the film captures the weight of choices and the uneasy boundary between necessity and morality.

This article explores the central themes of this darkly tragic and sharply satire work.

OUR SPONSOR OF THE DAY : NEONNIGHT.FR

The Plot

No Other Choice follows Yoo Man‑soo, a once‑stable paper industry worker whose life unravels after he’s suddenly laid off after 25 years on the job. With his family’s financial security collapsing and the job market closed off, Yoo Man‑soo becomes desperate to secure work again.

Concluding that he can only improve his odds by eliminating the competition, he concocts an increasingly extreme and darkly comic plan to murder other job applicants — a decision that spirals into violence, satire, and moral collapse as he confronts the brutal realities of economic insecurity and survival under capitalism.

The Core themes of No Other Choice

At its heart, No Other Choice is about what happens to a human being when society removes all dignified options and still expects moral behavior.

It’s a film about constraint, not freedom.

1. Work as identity

In the film, Yoo Man‑soo’s sense of self is deeply intertwined with his job. His career defines:

- His social status — the house, possessions, and respect from peers are tied to his managerial role.

- His purpose — providing for his family and being a “useful” member of society gives him meaning.

- His moral framework — the boundaries he observes, and even his ethical compromises, are structured around keeping his place in the workforce.

When he loses his job, it’s not just income that disappears; the core of his identity begins to crumble. This explains why Yoo Man-soo, like the other applicants, refuses to pursue work he perceives as beneath his qualifications or even remotely disconnected from the paper industry.

2. The psychological impact of losing a job

Man‑soo’s descent illustrates how deeply modern societies link human value to function:

- Desperation drives him to extreme, absurd, and morally compromised actions.

- The film portrays his anxiety, humiliation, and sense of invisibility, showing how unemployment strips not only security but dignity.

- His struggle is compounded by the fact that the “system” measures worth by productivity rather than inherent human value.

3. Satire and social critique of capitalism

Park Chan‑wook exaggerates these effects to critique a system where:

- Workers are interchangeable and replaceable.

- Economic structures dictate moral behavior.

- Status symbols (house, car, lifestyle) create illusions of stability that can vanish instantly.

The absurdity of Man‑soo’s plans underscores the extreme pressure that losing one’s job places on personal identity.

4. The illusion of free choice under capitalism

The title is the key.

The system tells the protagonist:

- You are free

- You have choices

- You are responsible for your success or failure

But in reality:

- Work is scarce

- Competition is ruthless

- Time is running out

- Dignity is conditional

So the “choice” becomes: Disappear quietly, or cross a moral line to survive.

This exposes a central contradiction: A system that demands morality while engineering desperation.

5. Moral collapse under structural violence

The film does not portray evil as:

- Sadism

- Cruelty

- Ideological hatred

Instead, evil emerges as:

- Rational

- Somehow Methodical

- Justified

- Quiet

- Even goofy

The protagonist doesn’t want to become monstrous. He becomes so because every humane option has been closed. This aligns with a very uncomfortable truth: Many immoral acts are committed not by monsters, but by cornered ordinary people.

6. Competition as dehumanization

The job market in the film is not neutral.

It:

- Pits identical humans against each other

- Reduces people to CVs and metrics (Pulp Man of the Year)

- Frames survival as “merit”

- Encourages self-erasure

Other people stop being: Fellow humans and become:

- Obstacles

- Variables

- Threats

This mirrors how modern systems quietly normalize dehumanization without violence — until violence appears “logical.” The film offers a glimpse behind the curtain, revealing the psychological forces at play.

7. Masculinity and worth

This is subtle but crucial. The protagonist’s identity is tied to:

- Being useful

- Providing

- Being competent

- Being respectable

When that collapses, he doesn’t just lose income — he loses ontological worth.

The film asks: What happens to a man when usefulness becomes the condition for dignity?

This connects deeply to:

- Male shame

- Status anxiety

- Quiet despair

- Rage without language

This strongly echoes the theme explored through the character of Jacob in Lee Isaac Chung’s Minari, though here it is taken to a far more extreme level.

8. Rationality without ethics

One of the most disturbing themes:

The protagonist remains:

- Calm

- Polite

- Somehow logical

His violence appears chaotic, not out of malice, but because he hesitates, fumbles, and never truly knows how to act, until the final act, where the progression becomes tragically clear.

There is no madness: the film shows how rationality instrumentalized by hopelessness and detached from ethics becomes a weapon, even when execution is hesitant and clumsy.

The violence is therefore progressive, uncertain, and never deliberately malicious—except for the final crime—highlighting the contrast between intention and outcome.Violence is chaotic — it is tedious even goofy at times. The killings feel human—flawed, hesitant, and real—rather than the work of a cold, clinical psycho.

9. Society as accomplice

Importantly, the film does not isolate blame.

The true antagonist is:

- A system that rewards outcomes, not methods

- A society that looks away

- Institutions that demand resilience but offer no mercy

The horror is not just what the man does but how understandable it becomes.

10. “No other choice” as existential tragedy

The title is not a defense. It’s an indictment.

The film asks:

- If a system leaves you with only immoral options, who is truly responsible?

- And more dangerously: How many people around us are closer to this edge than we admit?

The introduction explained

The movie’s introduction is undeniably cheesy, but in a way that feels surprisingly accurate. Even the color grading evokes the polished look of a family-oriented commercial.

Their home is practically an architect villa—they appear able to afford imported wines, curated designer goods, the latest tablets, hobbies and even an artistic career for their daughter that plays the cello on the rooftop. It’s like the American or Korean Capitalist dream, cranked all the way up.

The introduction shows the “perfect life” not as a natural state, but as:

- A visual and emotional baseline (like instagram and celebrities) against which the absurdity, moral compromise, and tragedy of the rest of the film are measured

- A performance of social aspiration

- A fragile construct dependent on career and societal function

It’s worth noting that the film uses the same piece, Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23, as in Terrence Malick’s The New World, during the scenes where John Smith lives among the natives and with Pocahontas—moments that carry the delicate, fleeting feel of a fragile dream.

Thus, from the very first scenes, the phrase “I have it all” establishes the film’s central tension: the gap between perceived success and underlying fragility—a contrast that fuels both the absurdity and the dark satire that follows.

It also resonates like a bucket list, framing life as a tally of achievements and possessions, reducing human experience to items that can be acquired—or abruptly taken away.

The ending explained

In the closing moments of No Other Choice, Park Chan‑wook offers a bitterly ironic resolution: although Yoo Man-soo has eliminated his competitors and secured a job, the position he now holds exists in a factory run almost entirely by AI and automation, leaving little human role for him to perform and hinting that even this “victory” may soon vanish.

This ending emphasizes that:

1. Yoo Man-soo’s efforts were ultimately futile

All the violence he committed didn’t lead to lasting security — the world he fought for has already moved on to technology that makes human labor unnecessary.

2. The job that validates him is already obsolete

Instead of supervising people, he essentially watches machines do all the work, suggesting that he’s replaceable even in the role he fought so hard to attain.

3. The film critiques a system where worth is tied to function

Yoo Man‑soo believed killing his rivals would restore his usefulness, but the automation of work shows that usefulness itself has become transient and hollow — you can be needed one moment and discarded the next.

Combined, these elements turn the ending into a satirical tragedy: Yoo Man-soo’s seemingly earned stability is undercut by the very forces that drove him to violence, illustrating how human identity and labor are being eclipsed by machines.

This automation acts as a mirror, showing that Yoo Man-soo embodies the same philosophy as the company—or the logic of capitalism itself—stripping humanity (obstacle) out of the equation.

The main characters

Yoo Man-soo

Yoo Man‑soo (Lee Byung-Hun) embodies the archetype of an upper‑middle‑class man, likely in management. Ironically, despite being an employee, he lives in a sprawling house that evokes the luxurious home of the Park family in Parasite, a space usually reserved for the ultra‑wealthy.

This contrast highlights how the modern middle class often aspires to emulate the lifestyle of the 1%, projecting wealth and status beyond their actual means riddled with debts, to justify their sacrifices.

Similarly, he occupies a conventional managerial role—one that, in reality, should be fairly easy to replace. If he were truly indispensable, his expertise would command such value that opportunities would naturally come to him. In the movie this inconsistency is explain by the slowly disappearing use of paper.

At his core, Yoo Man‑soo embodies the archetype of the holy fool—much like Homer Simpson—whose seemingly absurd schemes are ultimately guided by a moral purpose: providing for his family.

Though his plan is utterly abberant, the film uses it as a satirical metaphor, illustrating how, in a market that values people for their functions rather than their true identities, workers are ultimately interchangeable.

Unlike his calculated role in I Saw The Devil, Yoo Man‑soo is completely inept when it comes to eliminating the competition, producing a hilariously dark effect. He comes across less as skilled and more as a caricature of a persona representing societal expectations for behavior.

This contrast is especially striking in the scene where he drinks with Park Hee‑soon, when he breaks out of character and has to apologize for it but is rewarded for representing a form of extreme masculinity and authenticity.

Yoo Mi-Ri

Yoo Mi‑Ri (Son Ye‑Jin) portrays Yoo Man‑soo’s wife. Unlike the typical on-screen wife focused solely on comfort and insecurity, she is an active partner in supporting the family—willing to reduce expenses and personal pleasures, take on work, and even uphold the moral and practical sacrifices her husband makes.

In my view, this provides a far more accurate depiction of both the depth of a wife’s support and the way a man losing his job can ripple through the entire family.

The film suggests that while some women are genuinely loyal, they may at times betray trust out of desperation—and that, in this context, the wife acts almost like a psychologist an motivational coach guiding and supporting her unemployed husband through his struggles.

At some point she is even tempted to immorality as well in order to preserve her family, showing that the cost touches both parents not just men.

The Yoo’s kids

At first, the children are simply children, absorbed in their passions or escapist pursuits. But once their father enters survival mode, the son attempts to support the family financially, resorting to corrupt methods—yet faces no consequences for his actions.

Even more striking, he eventually reconciles with his theft partner as if nothing had happened, underscoring that in a system where immorality is tolerated, such transgressions carry little real repercussion even socially, reminiscing the end of the movie Carnage from Polansky.

By the film’s end, his daughter’s ability to play the cello illustrates how the sacrifices her father endured—moral, emotional, and practical—have created real opportunities and a protective foundation for her future. This reinforces the idea of how effective moral compromise can be within this society.

That even rare talent has to be supported by ultimately money or a 50,000 dollars cello and some really expensive specialized mentors.

Choi Seon-chul (the main target)

Choi Seon‑chul (Park Hee‑soon) portrays the man whose status and position make him the object of others’ desire and envy. His character is strongly reminiscent of Buddy Kane in American Beauty: a man who presents an immaculate, enviable persona to the world, yet lives a profoundly empty life beneath the surface.

He cannot even enjoy the comforts his status affords—like the serenity of his home in the nature with his wife, or simple pleasures such as using the nice exterior barbecue—highlighting the contrast between outward appearance and inner dissatisfaction.

Ultimately, the film shows a disconnect between what society admires and what truly brings fulfillment.

How does all this relate to reality?

This movie’s intro and ending creates a gap between cultural projection and lived reality.

1. Why Korean culture looks so attractive from the outside

South Korea exports:

- K-pop (perfection, youth, beauty, energy)

- Cinema & series (emotional depth, moral complexity)

- Fashion & design (clean, aspirational, modern)

- Technology & efficiency

This creates an image of:

- Discipline

- Sophistication

- Emotional intelligence

- Modern success

It’s highly curated. Korea is extremely good at aestheticizing struggle.

2. Why many Koreans are unhappy

At the same time, South Korea has:

- Extremely high pressure to perform

- Intense competition (school, work, appearance)

- Strong status hierarchy

- Long working hours

- One of the highest suicide rates in developed countries

- Very low birth rate

Many people live with:

- Chronic exhaustion

- Fear of falling behind

- Shame around failure

- Identity tied almost entirely to usefulness and status

This creates what some Koreans call:

“Hell Joseon” (헬조선)

3. The paradox: suffering fuels culture

This is uncomfortable but important:

- The same pressure that crushes people

- Also produces intense artistic output

Korean cinema (Park Chan-wook, Bong Joon-ho, Lee Chang-dong) is so powerful because it emerges from:

- Structural stress

- Moral contradiction

- Suppressed emotion

- Social cruelty

Art becomes:

- A pressure valve

- A coded critique

- A way to speak what can’t be lived freely

4. Why the world romanticizes it

From the outside:

- We consume the symbolic Korea, not the daily one

- The pain is packaged as style, drama, beauty

People admire:

- The results

- Not the cost

It’s similar to how:

- People love Paris but ignore French burnout

- Admire Silicon Valley but ignore mental collapse

- Love Japanese aesthetics but ignore overwork and loneliness

5. A deeper truth

A society can be culturally fascinating and psychologically brutal at the same time.

In fact, very often:

- The more controlled the surface

- The more tension underneath

6. The whole picture

What Korea makes visible in a concentrated way is something many modern societies share:

- A small group embodies the dream

- The illusion works because it’s partially true so the fantasy isn’t fake it’s incomplete and hide the cost (loss of privacy and autonomy and identity reduced to performance)

- The majority sustains the structure (workers)

- The dream is used as motivation and justification

OUR SPONSOR OF THE DAY : NEONNIGHT.FR

Conclusion

No Other Choice is a darkly satirical film, punctuated with moments of absurd humor, yet its themes remain deeply unsettling and almost disorienting. It resonates like few films do because it taps into one of humanity’s most profound fears: the loss of face, dignity, and social standing.

Through its biting critique of a system that equates worth with function, the film exposes how quickly stability, respect, and self-definition can crumble, forcing viewers to confront the fragility of both personal and societal identity.

The film reveals how easily we can be replaced and how moral compromise frequently becomes the foundation for sustaining the appearance of success—and, occasionally, real stability. It’s a bleak yet often accurate insight: society seems to demand that men trade inner alignment and ethical integrity for outward achievements and security.

Ultimately, the film reveals that in certain societies we have yet to inculcate dignity as an inherent right—something everyone deserves—while reserving admiration, status, and prestige as conditional. Instead, dignity itself is treated as something that must be earned through performance, productivity, or success—yet with the advent of AI, which increasingly replaces human labor, this may be the perfect moment to reconsider what it truly means to value a person.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings