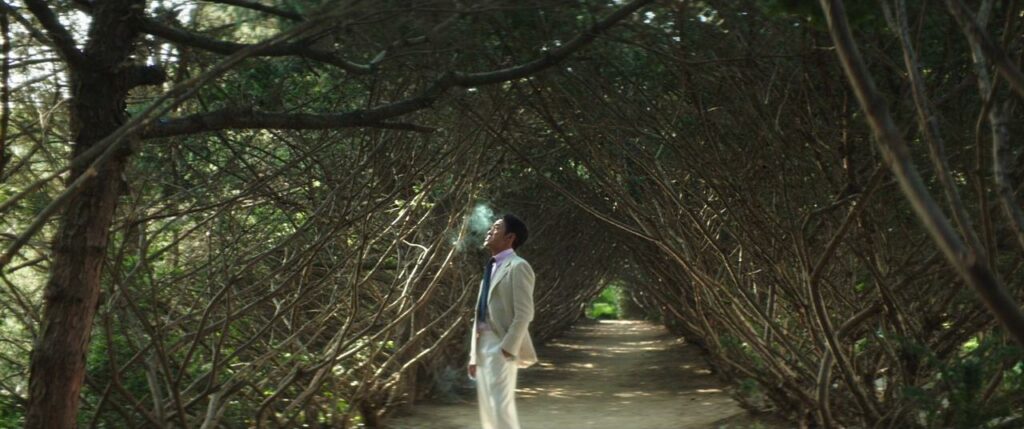

In The Handmaiden, Park Chan-wook explores desire as more than attraction—it’s a game of control, vulnerability, and hidden intentions.

Through Lady Hideko and Sook-hee, the film reveals how beauty, power, and longing intertwine, drawing us into a world where nothing is quite what it seems.

In this article, we explore why two seemingly opposite characters can be equally compelling and alluring.

OUR SPONSOR OF THE DAY : NEONNIGHT.FR

Plot Summary

Setting: 1930s Korea under Japanese colonial rule.

Main characters

- Hideko : an aristocratic Japanese heiress living in a secluded mansion, groomed to read erotic literature to wealthy men.

- Sook-Hee : a young Korean pickpocket recruited by a conman.

- Count Fujiwara : a Japanese conman planning to marry Hideko and steal her fortune.

Story outline

- The Con: Sook-Hee is hired as Hideko’s maid to help Count Fujiwara trick Hideko into marrying him, intending to defraud her.

- Bonding & Romance: Sook-Hee and Hideko grow close; Hideko begins to trust her maid. They eventually fall in love.

- Reversals: The narrative is revealed in three parts, each uncovering hidden truths. It turns out Hideko and Sook-Hee are outsmarting the Count together, reversing the initial deception.

- Liberation: Hideko escapes her controlling uncle and the Count, reclaiming her wealth and agency, aided by Sook-Hee.

Major Themes

1. Power and Oppression

- Hideko is initially trapped by patriarchal, colonial, and familial control.

- The story examines how social hierarchies and gender roles control women’s bodies and choices.

2. Illusion vs. Reality

- The film constantly plays with deception: lies, schemes, and hidden motives.

- Characters wear metaphorical and literal masks; nothing is as it seems.

3. Eroticism as Power

- Sexuality is not just desire—it’s a tool of manipulation, survival, and liberation.

- Hideko’s and Sook-Hee’s erotic and sensual performances reveal the interplay between control and agency.

4. Class and Cultural Tensions

- Highlights differences between Japanese colonizers and Korean locals, and the aristocracy vs. the lower class.

- Explores how colonial and social hierarchies intersect with gender and wealth.

5. Love and Liberation

- Beyond manipulation, the story is about genuine connection, trust, and solidarity between Hideko and Sook-Hee.

- True love becomes a form of resistance against oppressive systems.

6. Identity and Rebellion

- Hideko’s transformation from passive object to active agent mirrors the broader theme of reclaiming one’s identity and autonomy.

Cinematic style

- Highly visual, with meticulous framing, color symbolism, and erotic yet restrained cinematography.

- Music, set design, and costume reinforce power dynamics, tension, and sensuality.

- Narrative structure with multiple points of view mirrors the theme of deception and revelation.

A closer examination of desire’s dual nature

1. Lady Hideko — the cultivated / forbidden desire

Hideko is desirable because she represents rarity, refinement, and repression.

Why she attracts:

- Aristocratic beauty: porcelain skin, controlled gestures, refined speech.

- Distance: she is untouchable, secluded, curated.

- Eroticism through restraint: her sexuality is taught, performed, and controlled.

- Aestheticized suffering: she carries melancholy, trauma, and fragility.

Psychologically, she embodies:

- Desire for the unreachable

- Desire filtered through culture, art, and taboo

- The erotic charge of what is forbidden and controlled

Hideko is desirable because she is rare and constrained, like a priceless object locked behind glass.

2. Sook-hee — the raw / living desire

Sook-hee is desirable because she represents life force, warmth, and instinct.

Why she attracts:

- Earthy beauty: expressive face, physical presence, spontaneity.

- Sexuality without pretense: desire that emerges naturally, not performed.

- Emotional availability: laughter, anger, tenderness, impulsiveness.

- Moral vitality: she feels alive, not curated.

Psychologically, she embodies:

- Desire for authentic connection

- Desire grounded in touch, humor, and warmth

- The eroticism of life itself, not its representation

Sook-hee is desirable because she feels real, accessible, and alive.

3. Why we are attracted to both

Because humans are divided.

We desire:

- Elevation and embodiment

- Refinement and instinct

- Fantasy and truth

Park Chan-wook understands this deeply.

In symbolic terms:

- Hideko = desire shaped by culture

- Sook-hee = desire shaped by nature

Or:

- Hideko = the gaze

- Sook-hee = the touch

Neither alone is complete.

4. The core twist: desire becomes liberation

The film’s brilliance is that:

- Hideko learns to feel

- Sook-hee learns to see

- Desire stops being exploitative and becomes mutual

Their union dissolves:

- Male voyeurism

- Ownership of female bodies

- Desire as domination

They become desirable to each other, not as symbols, but as subjects.

5. Why the film stays with you

Because it doesn’t ask:

“Which woman is more desirable?”

It asks:

“What kind of desire is humane?”

And answers:

Desire that is chosen, shared, and embodied, not imposed or aestheticized for power.

In one sentence:

Both Hideko and Sook-hee are desirable because they represent two halves of human longing — the refined dream and the living body — and The Handmaiden is about reconciling them without domination.

If you want, we can also explore:

- how this maps to masculinity

- why male characters desire control, not intimacy

- or how this mirrors modern beauty culture and social media

Desiring Without Surrendering

How this is reflected in masculinity

In The Handmaiden, masculinity is almost always associated with the gaze, possession, and control, and rarely with presence or vulnerability.

The male characters do not so much desire women as what these women represent: status, rarity, symbolic domination.

Masculinity is constructed as a form of distance:

- looking rather than touching

- possessing rather than encountering

- organizing rather than feeling

It is an anxious masculinity, one that shields itself behind structures (money, culture, codified eroticism) in order to avoid any real emotional exposure.

Why male characters desire control rather than intimacy

Because intimacy implies a loss of control.

In the film, male desire is mediated through:

- erotic readings,

- staging and performance,

- the commodification of the female body.

This allows desire to be consumed without involvement.

Control replaces intimacy because it feels safer: it does not threaten identity, power, or ego.

Intimacy, by contrast, requires:

- reciprocity,

- vulnerability,

- transformation.

This is precisely what the male figures refuse—and that refusal condemns them to a form of emotional sterility.

How this reflects modern beauty culture and social media

The film’s dynamic feels strikingly contemporary.

Today, beauty is often:

- staged rather than lived,

- watched rather than shared,

- optimized rather than embodied.

Social media reproduces the same pattern:

- the body becomes an image,

- desire becomes a performance,

- value becomes a metric.

Aesthetics are celebrated, but the risk of real presence is avoided.

As in The Handmaiden, this creates a tension between:

- cultivated, visible, controlled beauty,

- and living, unpredictable, relational beauty.

The film shows that when desire is reduced to image or power, it becomes violent or empty.

When desire is shared, chosen, and embodied, it becomes liberating.

In summary

The Handmaiden is not only about female desire—it is a critique of a masculinity that confuses desiring with possessing, and of a culture that prefers aesthetic control over human encounter.

That is why the film resonates so strongly today: it does not ask what is beautiful, but how we desire—and at what cost.

Hideko as a Status symbol

Hideko herself is not just a woman in the story; she is capital, status, and symbolic power wrapped in a human body.

Let me break it down cleanly.

Hideko as a status symbol, not a person

For the men around her (Uncle Kouzuki, Count Fujiwara, the doctors, collectors):

- Hideko’s fortune = economic power

- Hideko’s aristocratic lineage = cultural legitimacy

- Hideko’s body = spectacle, possession, and proof of dominance

Owning Hideko is not about love or even desire alone — it is about validation in the eyes of other men.

In other words:

“If I possess her, I am somebody.”

This is classic male homosocial validation: men competing for status through women, not intimacy with women.

Hideko’s humanity confiscated

Hideko has all the inner qualities of a full human being:

- intelligence

- sensitivity

- erotic capacity

- imagination

- will

But those qualities are systematically extracted from her and repackaged as spectacle.

She is reduced to:

- a symbol (aristocracy, purity, wealth)

- a container (fortune, lineage)

- a performance object (readings, rituals, pornographic scripts)

Her body speaks, but her subjectivity does not.

So her humanity is:

- suspended

- curated

- immobilized

She becomes something closer to a museum artifact that breathes.

That’s why she feels cold, distant, almost unreal at first — not because she lacks humanity, but because she has been forced to dissociate from it to survive.

The fortune as symbolic masculinity

Hideko’s wealth functions like:

- A trophy

- A seal of legitimacy

- A shortcut to aristocratic power

Fujiwara doesn’t want to be noble — he wants to be seen as noble.

Marrying Hideko is a social hack: instant elevation.

Her fortune isn’t just money; it is symbolic recognition.

Why Hideko is trapped

Hideko is:

- Educated, refined, intelligent

- Yet treated as immobile capital

She is curated, displayed, trained — like a rare artifact.

The men’s obsession reveals something brutal:

They don’t want her subjectivity.

They want what she represents to other men.

That’s why her suffering is invisible to them.

Contrast with Sook-hee

This is where Park Chan-wook is surgical.

- Hideko = symbolic, aristocratic, frozen beauty

- Sook-hee = raw, embodied, alive presence

Men want Hideko because she raises their rank.

Hideko wants Sook-hee because she restores her humanity.

This is not accidental — it’s the film’s moral axis.

The deeper critique

The film exposes how:

- Patriarchal systems turn women into status currencies

- Masculinity becomes performative and empty

- Desire is corrupted by male-to-male comparison

Hideko’s escape is radical because she removes herself from the symbolic economy altogether.

When she leaves with Sook-hee, she doesn’t just escape abuse — she collapses the men’s status game.

In one sentence

Hideko and her fortune are not objects of love, but mirrors in which men try to see themselves as powerful — and the film destroys that illusion.

Why did it take over 1,500 women to find the perfect Sook-hee?

The “aristocratic beauty” of Lady Hideko is more codified and reproducible: refined posture, delicate gestures, porcelain-like features, cultivated poise. It’s a type of beauty that can be taught, emulated, or found among a larger pool of trained actors or models.

By contrast, Sook-hee’s raw, kinetic beauty is less formulaic. It’s in the way she moves, reacts, and inhabits the world—her energy, subtle confidence, and natural charisma. That kind of presence can’t easily be taught or imitated; it has to be found in the person themselves, which explains why Park Chan-wook needed to see thousands of candidates to find the “perfect fit.”

It’s like aristocracy can be mimicked, but authenticity can’t. That tension between the reproducible and the irreplaceable is part of what makes the dynamic between the two protagonists so hypnotic.

This is precisely why luxury brands have shifted their focus from aristocratic elegance to authentic expression.

OUR SPONSOR OF THE DAY : NEONNIGHT.FR

Conclusion

In The Handmaiden, the interplay of desire, power, and identity reveals that attraction is never one-dimensional. Sook-hee and Lady Hideko embody contrasting forms of beauty—raw versus cultivated—yet both hold equal allure, each drawing us into a world where appearances, intentions, and emotions are in constant negotiation.

Their magnetism lies not only in their physicality but in the tension of control and vulnerability, dominance and submission, that they navigate with every glance and gesture. Ultimately, the film reminds us that desire is as much about power and perception as it is about intimacy, and that true fascination often resides in the space between opposites.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings