American Beauty isn’t just a film about rebellion or midlife crisis. It shows what happens when people perceive the emptiness of a life shaped by appearances, routines, and expectations — and how small moments of presence can break through it.

Each character responds differently: denial, performance, escape, obsession, control, or fleeting glimpses of real experience.

This article explores the film as a guide to escaping emptiness and restoring presence, through lived experience, symbolic existence, and the fragile path toward personal sovereignty. The film doesn’t judge its characters; it holds up a mirror, reflecting what it truly means to inhabit one’s own life.

OUR SPONSOR OF THE DAY : NEONNIGHT.FR

The Plot

American Beauty follows Lester Burnham, a suburban man who begins to question the routines and expectations that shape his life.

Around him, his family and neighbors each navigate their own struggles with desire, identity, and connection.

The film observes their lives with sharp insight, exploring the contrast between appearances and what lies beneath the surface.

Why the Script Feels Unfulfilling

Society depends on routines, roles, and shared expectations to keep life organized and manageable. While this structure can feel comforting, it can also make it harder to fully inhabit our own lives.

By favoring stability over presence, conformity over choice, and appearances over genuine experience, the daily script can quietly limit the deeper satisfaction that comes from risk, curiosity, and living according to one’s own values.

The characters

Lester Burnham: Awakening Late, Feeling Fully

Lester begins largely caught in symbolic existence: defined by his job, suburban routine, sexual frustration, and quiet resentment. He is numb more than miserable, which makes his life feel hollow.

His “awakening” starts in ways that seem misdirected: quitting his job, lifting weights, chasing desire. On the surface, it may look juvenile or even absurd — and in part, it is. Yet beneath these gestures, something authentic emerges: he begins to speak truth, reconnect with his body, and refuse the small humiliations that have shaped his life.

Lester re-engages with life. By the end, he releases desire, resentment, and performance. His final moment is quiet, lucid, and fully present. He dies with a sense of wholeness, having glimpsed the richness of life, even if most of his adult years were lived under the weight of emptiness.

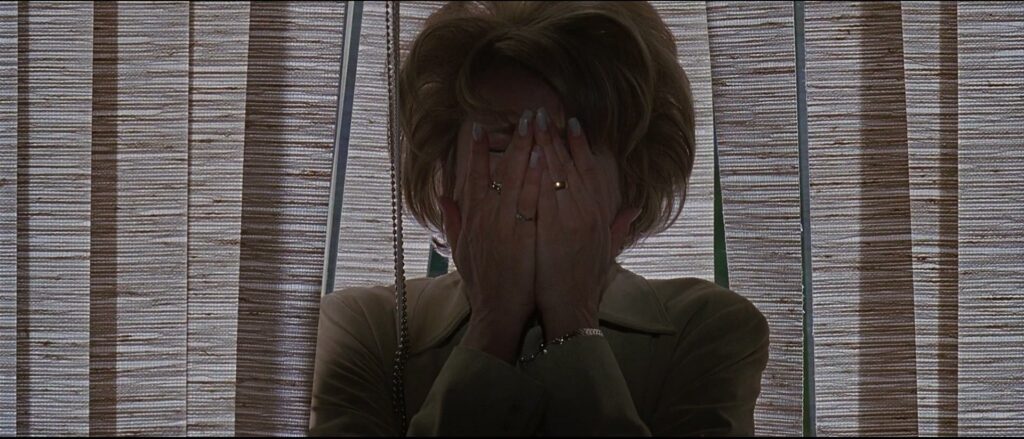

Carolyn Burnham: Bound by the Symbolic

Carolyn is perhaps the clearest portrait of life lived through symbols in the film.

Success, appearance, self-improvement, and constant positivity become a kind of armor against emptiness. She believes that discipline and image will protect her from despair. Yet they cannot, because:

- She rarely risks speaking truth.

- She rarely allows herself to be vulnerable.

- She rarely steps outside the roles she performs.

Her tragedy is not cruelty, but a deep commitment to a life built on appearances. Carolyn is competent, functional, and driven to be admired, yet beneath it all, a quiet hollowness persists.

Jane Burnham: Learning to Be Seen

Jane lives in comparison and reflected identity. She is still discovering herself, aware more of who she is not than who she is. She feels unseen and uncertain, yet also hesitant to let herself truly be seen because it doesn’t match the collective expectations.

Her emptiness does not come from conformity, but from a lack of self-authorship. Her relationship with Ricky is not fully love, but a first taste of recognition: he sees her without expecting her to perform. Through him, she begins to imagine another way of being.

Jane stands at the threshold, no longer asleep, beginning to inhabit her own presence.

Ricky Fitts: Towards Freedom

Ricky is often seen as an odd person on the surface but “free” in reality, and in many ways he is. He experiences life intensely, directly, and with an aesthetic sensitivity, noticing beauty where others might not. He is present, curious, and unafraid of what others avoid, embodying a form of pure lived experience.

Yet his freedom is not fully self-directed because of his age. He tends to evade authority rather than fully transcend it, and he observes life through his camera more than he shapes it. He takes real risks — dealing illicitly, saving money, planning to leave home for New York and of course by approaching Jane.

Ricky is free from symbols and appearances. He is a witness and a participant, exploring the boundary between experience and self-authorship. His choices hint at a path toward autonomy, showing that lived experience can gradually move toward intentional, self-directed life.

Colonel Fitts: Hidden Truths, Quiet Pressure

Colonel Fitts shows what can happen when symbolic order dominates life at the expense of lived truth.

Discipline, masculinity, patriotism, and control shape his world, but they also suppress desire, fear, and vulnerability. His rigidity is not strength, but a response to inner tension. When his repressed truths emerge, they are unarticulated and unintegrated, expressing themselves in moments of destructive intensity.

He embodies a form of emptiness born of denial:

- Truth left unspoken

- Desire constrained

- Identity tightly enforced

His struggle reminds us of the cost of ignoring what is alive and present within ourselves.

Angela Hayes: Projected Wholeness, Quiet Void

Angela perform to be desired because she has learned to equate it with value.

She often confuses attention with worth, sexuality with power, and fantasy with identity (2.0 economics). Her confidence acts as a kind of armor, and her seduction is a performance shaped by expectation. Beneath the performance, she is fragile, uncertain, and very young. Her emptiness is not a failing, but a reflection of what she has been taught, to be wanted, but not truly seen.

She shows what can happen when a person learns to perform for recognition rather than to inhabit their own presence.

Buddy Kane: The Idealized Collective Projection

In order to be successful, one must project an image of success at all times. Buddy Kane

Buddy Kane embodies the ideal of success: confidence, wealth, charm, and effortless masculinity. For Carolyn, he represents the life she believes might bring her fulfillment. But Buddy is not a person he is a symbol, a projection of desire shaped by status and recognition (a marketing ideal to sell).

He illustrates the illusion that fulfillment can come from performance alone. He appears complete because he is perfectly aligned with the script: success, control, and social approval. Yet this perfection is hollow, because it is contradictory with his lived experience (divorce and looking to connect with Carolyn).

In this way, Buddy Kane is quietly influential to Carolyn by suggesting a seductive, misleading promise: that emptiness can be solved by becoming a better symbol.

The plastic bag scene

The scene shows Ricky Fitts film of a plastic bag tumbling and dancing in the wind. To him, the bag is mesmerizing — chaotic, unpredictable, alive. While it seems mundane or even worthless to most people, Ricky sees poetry, motion, and presence in it.

This moment captures lived existence in its purest form:

- There is no symbolic meaning attached (no status, no image, no approval).

- There is no script to follow, it is simply attention and presence in the moment.

- Ricky’s fascination shows how beauty and significance can exist outside societal expectations.

Ricky finds meaning in raw, unstructured reality.

In short, the plastic bag represents:

- Chaos and freedom

- The wonder in the ordinary

- The possibility of experiencing life fully, without needing to perform or succeed

It’s a visual metaphor for the film’s central question: can we pay attention to life as it is messy, fleeting, and beautiful instead of only chasing symbolic or curated ideals?

The Film’s Core Truth

American Beauty is not about rebellion.

It’s about misplaced attempts to escape emptiness.

Some characters:

- cling to symbols

- others flee into sensation

- a few approach truth too late

- almost none reach sovereignty

And that’s the point. Wholeness is rare because it requires:

- presence

- risk

- truth

- authorship

Most people settle for one and avoid the rest.

What Makes a Person Feel Empty

Emptiness isn’t sadness. It’s disconnection from lived reality and self-authorship.

1. Living Through Symbols Instead of Experience

- Status without substance

- Identity without action

- Titles without risk

- Image without embodiment

- Being seen more than being

You exist as a representation, not a presence.

2. Safety Without Meaning

- Comfort with no stakes

- Routine without chosen purpose

- Predictability without growth

- Risk avoidance as a life philosophy

The nervous system stays calm; the soul atrophies.

3. Passive Consumption

- Endless scrolling

- Endless purchasing

- Watching others live

- Borrowed adventure

- Borrowed outrage

- Borrowed identity

You feel busy, informed, stimulated — but not alive.

4. External Validation as Fuel

- Needing approval

- Needing agreement

- Needing applause

- Needing reassurance you’re “doing it right”

The self never consolidates. It leaks outward.

5. Scripted Living

- “Next step” thinking without questioning

- Inherited goals

- Socially approved milestones

- Fear of deviating

Life feels correct… and strangely unbearable.

6. Avoidance of Truth

- Emotional anesthesia

- Rationalization

- Irony as defense

- Cynicism as protection

You survive by not looking too closely.

7. Fragmentation

- One self online

- One self at work

- One self at home

- None of them fully real

No center. Just masks.

8. Adventure Without Consequence

- Gamified challenge

- Simulated risk

- Curated difficulty

- “Hard things” that can be quit anytime

It feels impressive, but it doesn’t transform you.

What Actually Makes a Person Feel Whole

Wholeness isn’t happiness. It’s alignment between perception, action, and authorship.

1. Presence in the Body

- Physical engagement

- Sensation

- Fatigue

- Discomfort

- Real effort

You are here, not narrating from a distance.

2. Chosen Risk

- Stakes you didn’t outsource

- Consequences you accept

- Uncertainty you step into willingly

Courage isn’t bravado — it’s consent.

3. Self-Authored Meaning

- Values you chose

- Not inherited, not reactive

- Not explained — lived

Life stops asking permission.

4. Truth Over Comfort

- Seeing clearly, even when it costs

- Not editing your story for approval

- Not hiding the difficulty

Integrity replaces reassurance.

5. Responsibility

- For choices

- For outcomes

- For your own direction

Blame disappears. Power returns.

6. Real Connection

- Being seen without performance

- Shared reality, not curated identity

- Presence with others, not distraction

Depth replaces novelty.

7. Creative Expression Rooted in Experience

- Making from lived material

- Art that costs something

- Work that reflects who you’ve become

Creation integrates the self.

8. Acceptance of Limits

- Mortality

- Imperfection

- Uncertainty

- Loss

Paradoxically, this stabilizes the self.

9. Coherence

- Your actions match your perception

- Your words match your life

- Your inner and outer selves align

No split. No role-play.

The Core Law

Nothing that bypasses risk, presence, and authorship produces wholeness. Nothing that avoids consequence produces meaning.

That’s why:

- Scrolling never fills anyone

- Status never satisfies for long

- Comfort without choice becomes a prison

- Simulated adventure feels hollow

- Truth, even painful truth, feels grounding

The Importance of Life Affirmation

The will to power, life affirmation, and self-affirmation are essential for living fully, because they anchor existence in action, choice, and the recognition of oneself. Embracing the will to power does not mean domination or control, but the quiet assertion of oneself as an active participant in life — shaping one’s path rather than drifting along.

Life affirmation brings acceptance of existence as it is, welcoming its challenges, contradictions, and fleeting moments of beauty, instead of escaping into distraction or conformity. Self-affirmation completes this process, allowing one to honor and validate personal values, desires, and presence, rather than relying on symbols, status, or the approval of others.

Together, these practices transform life from passive observation into engaged participation, creating space for authenticity, presence, and the deep sense of fulfillment that comes from truly inhabiting one’s own existence.

Why Buddy Kane isn’t American beauty’s protagonist ?

Buddy Kane isn’t the protagonist because American Beauty isn’t a commercial or a story about what society wants us to admire, it’s a story about what it truly means to live and be present (to experience life to the fullest). Buddy represents the biased collective ideal (socially imposed ideal): confidence, wealth, charm, control, effortless “success.” He embodies the image that society, especially capitalist society, teaches us to desire.

But here’s the crucial point: being ideal in the eyes of others is not the same as being alive. Buddy Kane never risks, never struggles, never confronts emptiness, fear, or truth. He exists as a symbol, a reflection of what others think they want — particularly Carolyn. He doesn’t inhabit life fully; he performs success (as an actor) flawlessly. There is no interior life, no vulnerability, no self-discovery.

The protagonist must navigate emptiness, confront desire, and reclaim presence — that’s Lester, Ricky, Jane, even Carolyn in her own way. They engage with life’s chaos, risk, and beauty. Buddy can’t lead that journey because he is already “finished” on society’s terms. His perfection is hollow; it’s an ideal to measure oneself against, not a life to inhabit.

In short: Buddy Kane is not the protagonist because the story is about awakening, presence, and authenticity — things he can neither teach nor embody. He is the mirror of social desire, not the path to wholeness.

Playing the game is inevitable, sometimes even important to derive pleasure from it— what matters is not identifying yourself with the outcome.

OUR SPONSOR OF THE DAY : NEONNIGHT.FR

Conclusion

At the ending of American Beauty, Lester reflects quietly on his life in a moment of clarity and presence. He doesn’t focus on possessions, status, or regrets about others’ expectations. Instead, he remembers the small, ordinary things that truly mattered — moments of beauty, simplicity, love, connection, and being fully alive.

He thinks about:

- Lying on the grass as a child, watching falling stars

- Watching the leaves moving on a tree

- His grandmother’s hands and their wrinkles

- The first time he saw his cousin’s brand-new Firebird

- His daughter Jane

- His wife Carolyn

It’s a moment of lucid acceptance: Lester recognizes life as it really was, both painful and beautiful, and he dies appreciating the fullness of lived experience, even if it came late and, instead of clinging to beauty, he lets it flow through him, appreciating the fullness of lived experience even if that understanding came late.

Ultimately, emptiness can be softened by fully inhabiting the life you have — noticing the small, vivid moments, embracing connection, aligning your choices with your values, stepping willingly into risk, and accepting the limits that shape your existence. Presence, in body and mind, transforms life into something felt and real.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings